From The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Before the eclipse, that will bring thousands to Southern Illinois, I will be sharing several news stories and articles about it. The first is explaining some information about eclipses in general – Steve

What is an eclipse?

A solar eclipse over Indonesia in March, 2016. (AP file photo)

An eclipse occurs when the Sun, Earth, and Moon move into alignment with each other. One of the bodies blocks the view of another and creates a shadow. There are 2 different types of eclipses: solar and lunar. A lunar eclipse happens at nighttime and occurs when the Earth passes between the Sun and the Moon creating a shadow on the Moon. These types of eclipses occur roughly 2 to 4 times per year. A lunar eclipse will generally last for a few hours.

What To Expect

On Monday, August 21, 2017, all of North America will be treated to an eclipse of the sun. Anyone within the path of totality can see one of nature’s most awe inspiring sights – a total solar eclipse. This path, where the moon will completely cover the sun and the sun’s tenuous atmosphere – the corona – can be seen, will stretch from Salem, Oregon to Charleston, South Carolina. Observers outside this path will still see a partial solar eclipse where the moon covers part of the sun’s disk.

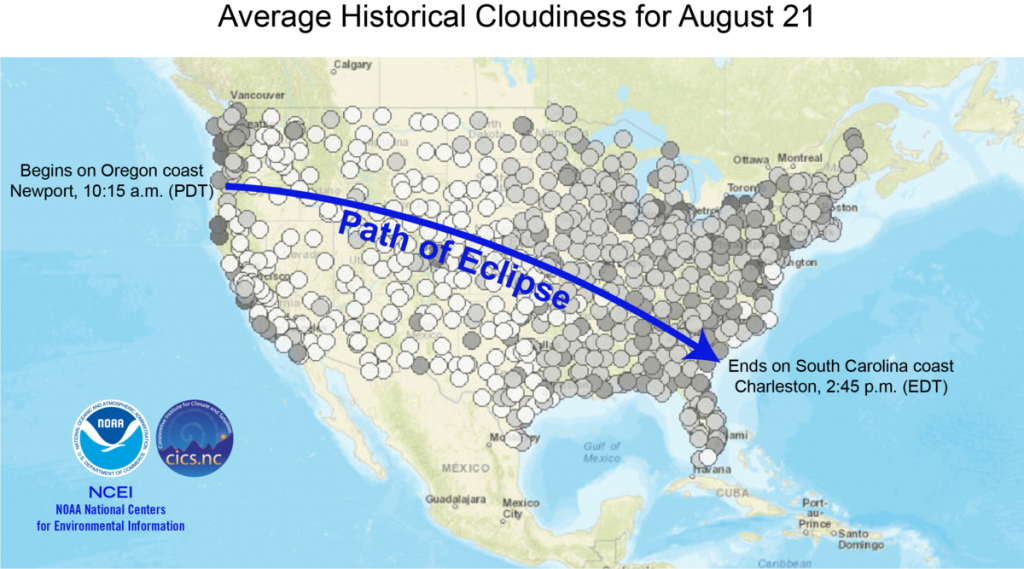

One of the biggest shows of the summer won’t require a ticket. However, the rare total solar eclipse crossing the country on August 21, from Oregon to South Carolina, must contend with the bane of sun seekers: the potential for cloudy weather.

We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi RiverHistorically speaking, cloudiness may factor into each location’s chance for a good viewing. NOAA’s NCEI and the Cooperative Institutes for Climate and Satellites–North Carolina (CICS-NC) reviewed past cloud conditions for August 21. We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi River.

One of the biggest shows of the summer won’t require a ticket. However, the rare total solar eclipse crossing the country on August 21, from Oregon to South Carolina, must contend with the bane of sun seekers: the potential for cloudy weather.

We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi RiverHistorically speaking, cloudiness may factor into each location’s chance for a good viewing. NOAA’s NCEI and the Cooperative Institutes for Climate and Satellites–North Carolina (CICS-NC) reviewed past cloud conditions for August 21. We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi River.

One of the biggest shows of the summer won’t require a ticket. However, the rare total solar eclipse crossing the country on August 21, from Oregon to South Carolina, must contend with the bane of sun seekers: the potential for cloudy weather.

Historically speaking, cloudiness may factor into each location’s chance for a good viewing. NOAA’s NCEI and the Cooperative Institutes for Climate and Satellites–North Carolina (CICS-NC) reviewed past cloud conditions for August 21. We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi River

We found that the coasts could be susceptible to cloudier conditions and that increased cloud cover may be possible as the eclipse travels across the country east of the Mississippi River

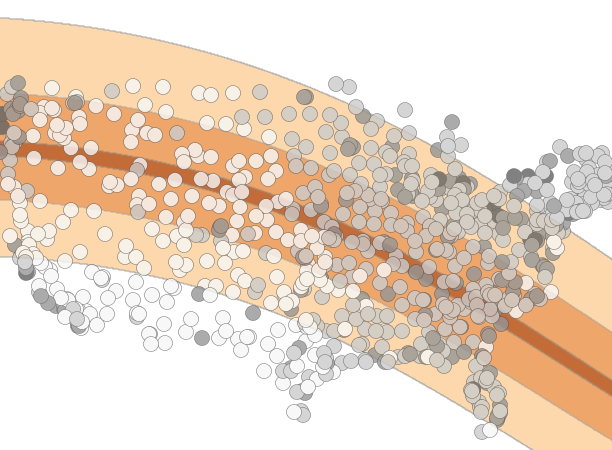

The darker the dot, the greater the chance for cloudiness at the hour of peak viewing during the total solar eclipse on August 21, 2017. Dots represent automated weather stations that reported the cloudiness data and show the 10-year cloudiness average for August 21, 2001–2010. Map developed by CICS-NC in cooperation with NOAA NCEI, Deborah Riddle. Notice that over this time, Southern Illinois has the least chance of cloudiness.

Although the picture doesn’t particularly bode well at the coasts of Oregon and South Carolina, the chance for clearer skies appears greatest across the Intermountain West. If historical conditions hold true, Rexburg, Idaho, a two-hour drive west of Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park, has a good chance for clearer skies. Casper, Wyoming, also holds promise. Other historically clear locations include Lincoln, Nebraska, and Carbondale, Illinois.

Historical cloudiness increases as the path curves southeastward across the Plains, making viewing the rare event potentially rarer as it moves toward the East Coast. This is the first time since 1979 that a total eclipse has crossed the United States and the first time since 1918 that one will travel coast to coast. Everyone in the 50 states will be able to experience at least a partial eclipse, depending on weather, but no other country falls in the path of the total eclipse.

Try Our Interactive Eclipse Map

Our interactive map provides greater detail about viewing the eclipse across the nation. The map lists a “viewable” percentage for each reporting location. The viewable percentage represents the likelihood of skies being clear enough for the eclipse to be visible. A higher percentage means a viewer is more likely to have a view unobstructed by clouds. Also, a bar chart shows the probabilities for five types of cloud cover: clear (no clouds), few, scattered, broken, and overcast. Percentages are derived from averages of each type of cloud cover.

Only an estimated 12 million people live within the relatively narrow area of the total eclipse. (NOAA map)

Take Newport, Oregon, for instance, the first land-based weather station location in the path of the full eclipse. The eclipse will occur there at approximately 10:15 a.m. local time (17:15 UTC). The viewable percentage is 44 percent, meaning there’s a 56 percent chance that viewability will be adversely affected by clouds. Keep in mind the percentage is an estimate of average conditions, not a guarantee for this year.

Only an estimated 12 million people live within the relatively narrow area of the total eclipse. However, several major cities and five state capitals fall within the path of totality—the narrow band where the moon completely blocks the sun’s face. Visit the CICS-NC interactive map (link is external) to search for an optimal viewing location by zip code.

Find a Seat for the Total Eclipse

From its first appearance over the Pacific Northwest in midmorning, the eclipse will last approximately 90 minutes, ending shortly after 2:45 p.m. local time (18:45 UTC) on the South Carolina coast near Charleston. Here’s a partial list of towns and cities on the path of totality from west to east along with estimated local times for peak viewing of the total eclipse, followed by the average historical cloudiness percentage (state capitals in bold; asterisks indicate larger airports):

| Illinois | Carbondale | 1:19 p.m. (CDT) | 80% |

| Kentucky | Paducah | 1:22 p.m. (CDT) | 77% |

| Chesterfield near St. Louis | 1:16 p.m. (CDT) | 61%

|

Eclipse Essential: Protect Your Eyes

The eclipse should only be viewed with protective eyewear designated for use during an eclipse. Ordinary sunglasses or 3D glasses lack sufficient protection. It’s important to take precautions when viewing the eclipse. The partial phases of the eclipse can last between 2 to 3 hours; at its longest, the total eclipse will last 2 minutes and 40 seconds.

Direct viewing of the partial phases can cause permanent damage to your eyes because of the intensity of the sunlight. The eclipse should only be viewed with protective eyewear designated for use during an eclipse. Ordinary sunglasses or 3D glasses lack sufficient protection. Also, avoid viewing through unfiltered cameras, telescopes, binoculars, or other optical devices.

However, if weather cooperates during the few minutes that the sun is completely eclipsed in totality, the brief interval is as safe to view as a full moon.

Safety Precautions

Looking directly at the Sun is unsafe except during the brief total phase of a solar eclipse (totality

), when the Moon entirely blocks the Sun’s bright face, which will happen only within the narrow path of totality.

The only safe way to look directly at the uneclipsed or partially eclipsed Sun is through special-purpose solar filters, such as eclipse glasses

or hand-held solar viewers. Homemade filters or ordinary sunglasses, even very dark ones, are not safe for looking at the Sun. To date four manufacturers have certified that their eclipse glasses and handheld solar viewers meet the ISO 12312-2 international standard for such products: Rainbow Symphony, American Paper Optics, Thousand Oaks Optical, and TSE 17.

Always inspect your solar filter before use; if scratched or damaged, discard it. Read and follow any instructions printed on or packaged with the filter. Always supervise children using solar filters.

- Stand still and cover your eyes with your eclipse glasses or solar viewer before looking up at the bright Sun. After glancing at the Sun, turn away and remove your filter — do not remove it while looking at the Sun.

- Do not look at the uneclipsed or partially eclipsed Sun through an unfiltered camera, telescope, binoculars, or other optical device. Similarly, do not look at the Sun through a camera, a telescope, binoculars, or any other optical device while using your eclipse glasses or hand-held solar viewer — the concentrated solar rays will damage the filter and enter your eye(s), causing serious injury. Seek expert advice from an astronomer before using a solar filter with a camera, a telescope, binoculars, or any other optical device.

- If you are within the path of totality, remove your solar filter only when the Moon completely covers the Sun’s bright face and it suddenly gets quite dark. Experience totality, then, as soon as the bright Sun begins to reappear, replace your solar viewer to glance at the remaining partial phases.

An alternative method for safe viewing of the partially eclipsed Sun is pinhole projection. For example, cross the outstretched, slightly open fingers of one hand over the outstretched, slightly open fingers of the other. With your back to the Sun, look at your hands’ shadow on the ground. The little spaces between your fingers will project a grid of small images on the ground, showing the Sun as a crescent during the partial phases of the eclipse.

A solar eclipse is one of nature’s grandest spectacles. By following these simple rules, you can safely enjoy the view and be rewarded with memories to last a lifetime.

Understanding the Historical Cloudiness Data

Our historical cloudiness data come from 10-year hourly climate normals for 2001–2010 measured at automated weather stations across the country on August 21, as close to the hour of the eclipse as possible. Availability of data determined the number of usable stations. The period 2001–2010 was chosen because a nationwide network of automated observing stations became operational in 1998. This 10-year timeframe allowed hourly normals computation for more than 800 stations.

However, many factors can influence cloudiness. Areas that experience higher humidity, such as coastal Oregon and the Southeast, are more likely to experience cloudy conditions. Other local factors may influence cloudiness and viewability as well, such as mountains and fog. Afternoon convection can also cause pop-up showers and storms. This helps explain the lower viewable percentages over the eastern half of the United States when the eclipse passes through early to midafternoon.

Keep a few other caveats in mind as you look at our maps. Automated weather stations only view clouds from the surface to 12,000 feet. Larger airports also typically have two cloud sensors (ceilometers) whereas smaller airports may only have one. Larger airports often have human observers that can see higher clouds. These differences mean that stations at larger airports tend to detect more clouds, so stations near each other may report different viewability percentages.

Ultimately, the cloudiness calculations are based on past observations, which are no guarantee of future outcomesUltimately, the cloudiness calculations are based on past observations, which are no guarantee of future outcomes. For predictions of actual conditions closer to the day of the eclipse, check your location’s forecast at NOAA’s Weather.gov as early as seven days prior to the event.

As Brady Phillips of NOAA’s Office of Communications notes, “Even the driest places on Earth experience clouds, fog, and rain.

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.